Antonin Besse: The Shadow Tycoon of Aden

Antonin Besse was somewhat of an enigma within high society—present yet elusive. His business ventures stretched from the dusty streets of Aden across the vibrant markets of Europe to the rugged terrains of Abyssinia, establishing him as a legendary figure in his era. Wealthier than renowned figures like Cowasjee Dinshaw and Paul Riès, he was the subject of widespread speculation but remained a mystery to most.

His knack for discretion was unparalleled; he believed that the less people knew about him, the more seamlessly he could navigate his affairs. Even those closest to him found it difficult to trace his origins, and the volume of rumours surrounding his life rivalled those found in celebrity gossip columns. This aura of mystery only added to his mystique, making him a topic of conversation and curiosity wherever his name was mentioned.

Tragedy soon struck when Antonin's father passed away, leaving a young Antonin, only seven years old, with his mother to care for six siblings. School did not hold his interest, perhaps explaining his eagerness to enlist in the military at the age of 18.

The family consisted of Antonin and his six siblings: three brothers, Joseph, Marcel, and Emile, and three sisters, Jeanne, Josephine, and Marie-Louise. His sister Jeanne married a Monsieur Selignac, and they had a large family of three sons and three daughters. One of Jeanne’s sons, Pierre, later married and had children but eventually divorced. Pierre's daughter, Michèle, married Roland Nungesser, who later became a member of the French Parliament and mayor of Nogent-sur-Marne. Jean, another of Jeanne’s sons, rose to become the managing director of a major insurance company in Paris. During the war, to retain his position, he had to research his family's origins in Carcassonne to demonstrate to the Vichy government and the Nazis that the family had no Jewish ancestry.

Among his brothers (Joseph, the eldest, Marcel, and Emile), Antonin had strained relationships with the two older ones. The specifics of Joseph’s career are unclear, but it was believed he became a cook or chef for an English nobleman. Marcel pursued a career as a chemist and bore a striking resemblance to Antonin. Known for his lifelong commitment to communism, he was affectionately dubbed “Red Uncle”. Emile, the youngest, would later work with Antonin in Aden during the early 1900s.

He spent his formative years in Montpellier and in around 1895, he enlisted in the French army for a four-year term. During his service, Antonin became severely ill, though the exact nature of his illness remains unclear. His military doctor, Dr. Bernard, was quite stern, asserting that Antonin would recover if only he adhered strictly to his prescribed regimen, which notably included a daily consumption of raw liver and a recommendation to relocate to a warmer climate post-service. Antonin, deeply respecting Dr. Bernard, followed these instructions meticulously.

The Besse family in Montpellier c.1885. Antonin is the tallest boy in the front

Antonin Besse was born on June 26 1877 into a modest family from Carcassonne, in southwest France. While he was still young, the family relocated to Montpellier, primarily due to his father’s health issues, which they hoped would improve with better medical care available there. Antonin's father owned a leather business that catered to local artisans such as saddlers and shoemakers.

This company, known for having once employed the poet Arthur Rimbaud as an assistant—a role Antonin was about to assume—offered modest compensation. Nonetheless, Antonin departed from Marseille on April 16, 1899, embarking on a three-year stint with the firm.

Located in the British colony of Aden, Monsieur Bardey’s business was predominantly engaged in exporting goods such as coffee from the nearby major producer Yemen, as well as hides, skins (mainly from goats), and incense. While there are indications that the company may have been involved in some import operations, details on this part of the business are limited.

Antonin proved to be a diligent worker, starting his days early and finishing late, quickly becoming knowledgeable about the coffee trade. However, he did not form a strong bond with his employer, Bardey. Once his contract ended, he didn't hesitate to start his own venture in Hodeida in early 1902 with some financial backing from his brother-in-law. That same year, he returned to France and successfully negotiated a significant loan from a bank to settle his debts, establish himself in Aden, and bring his brother Emile to assist with the business in Hodeida. By 1904, facing pressure from the bank for repayments, Antonin and his brother-in-law managed to negotiate an early and favourable settlement of the debt.

After completing his stint with Bardey & Co, Antonin decided to venture out on his own, setting up a business that thrived, especially in the goat skin trade. The demand for goat skins was high due to their use in glove-making—a booming industry at the time, as no self-respecting lady of the late 19th and early 20th centuries would be seen without gloves. This industry, primarily based in Millau, France, ensured a continuous demand for goat skins. However, post-World War I, the industry declined, turning Millau from a bustling town into a quieter locale, noted briefly in modern times for the impressive Viaduct of Millau designed by Norman Foster.

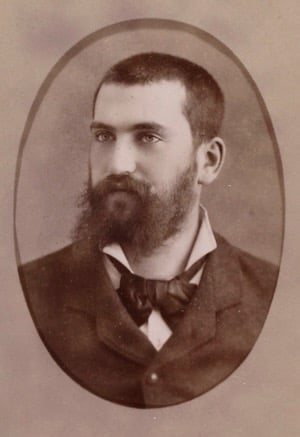

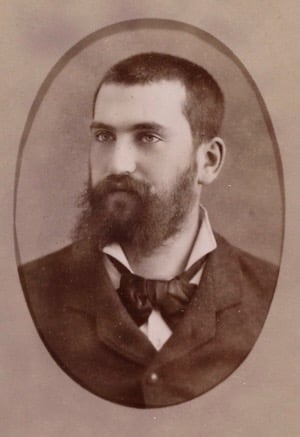

Alfred Bardey 1854-1934

After completing his military service, Antonin Besse was eager to follow his doctor's recommendation to live in a warmer climate for his health. In 1899, at the age of 22, he managed to convince his brother-in-law to lend him some money to buy necessary items like a trunk and appropriate clothing for his new role at Bardey & Co. in Aden.

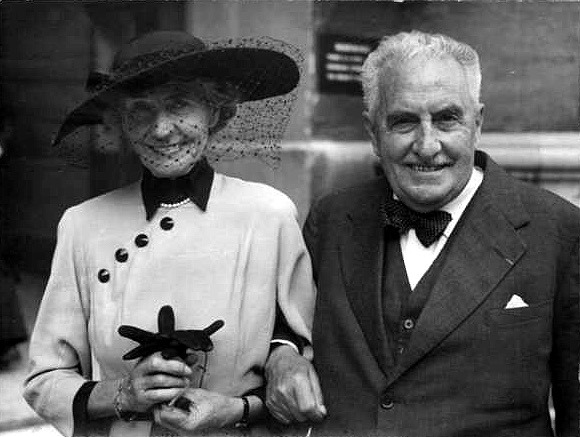

During his annual trips to France to meet clients, Antonin boarded a train in Lyon in 1907 and met Marguerite Hortense Eulalie Godefroid, a young Belgian woman traveling to the south of France. Their chance meeting blossomed into a romance fuelled by letters, leading to their marriage in April 1908. Marguerite's considerable wealth significantly boosted Antonin's business. The couple split their time between Brussels and Aden, having two children, Meryem and André. Despite his charm, Antonin was a harsh father, known for his sadistic tendencies towards his children.

The relationship took a severe hit when Antonin fathered a child, Ariane, with his secretary, Florence Hilda Crowther, who preferred to use the name Hilda. While Marguerite had tolerated his previous indiscretions, this was too much, leading to their divorce in 1922—an unusual and scandalous decision at the time. Following the divorce, Antonin married Hilda and they had four more children.

This tumultuous personal life did not hinder his business acumen. With Marguerite's initial investment, Antonin's business saw an impressive 750% increase in turnover in just the first year, showing a remarkable ability to blend personal audacity with business savvy. His later years with Hilda proved more stable, sharing both family life and business responsibilities, supporting each other through various personal and professional challenges.

Antonin & Hilda Besse

Antonin wasn't just a man of business; he truly embraced life with enthusiasm. Whether he was playing tennis, riding briskly, sailing through the waves, or climbing mountains, he did it with a passion. He also kept his mind engaged by delving into music and books as if they were going out of style, all while maintaining a look that was more akin to European high society than anything you’d expect from a desert trader.

Trying to sum up Antonin Besse's life in a few short paragraphs? It's simply not feasible. His life was so rich and multifaceted, you'd probably need an entire library to do it justice. It's surprising there hasn't been a film about him yet. So, what you’re reading here barely scratches the surface, offering just a glimpse into the remarkable saga of his life.

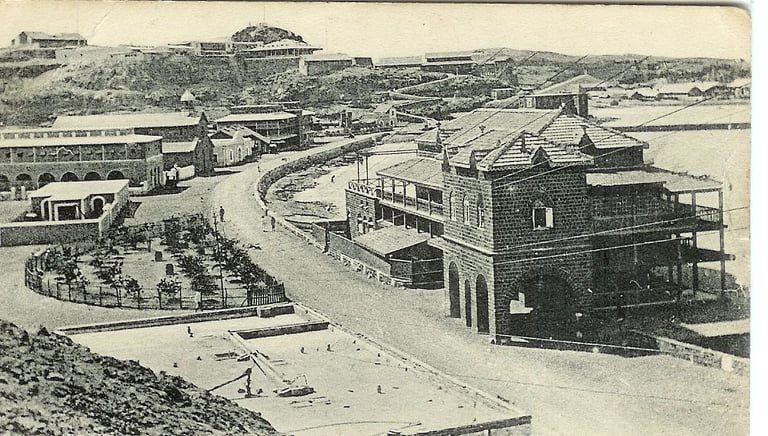

Antonin Besse's response to being rejected for membership by the Union Club in Aden underscores his independent character and robust self-esteem. Despite his vast commercial success and the social status he held in Aden, his exclusion from this prestigious club did not seem to perturb him significantly. This incident highlights his resilience and perhaps even his disdain for the traditional colonial establishments that might have viewed him as an outsider. Besse's indifference to the rejection could be seen as a reflection of his self-reliance and confidence in his own achievements, which were significant enough not to require validation from such social institutions.

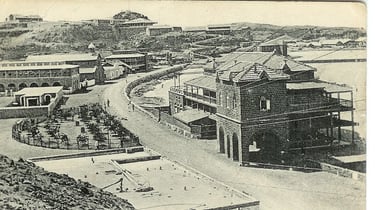

The Union Club. The semi-circle opposite was designed as a turning point for gharries.

His focus remained on his business enterprises and philanthropic efforts rather than social acceptance by colonial clubs. This resilience and focus on what truly mattered to him—his business acumen, the well-being of his employees, and later, his educational philanthropy—demonstrate a man more concerned with real-world impacts than social standing within the expatriate community. Such an attitude might have also contributed to his eventual decision to make substantial donations to educational institutions like Oxford, further indicating his preference for legacy and substance over social fraternities.

By 1914, Antonin had established his main office on Aidrus Road, Crater, complete with a sophisticated penthouse featuring numerous luxuries. Although he once sold this property to settle financial obligations, he managed to lease it back and maintained it as his operational base until his passing.

His entrepreneurial spirit did not wane with time. In 1934, Antonin acquired a struggling soap factory, revitalised it with modern machinery, and by 1937 had begun producing coconut oil. His ventures continued to expand, and in 1938, he opened a glycerine factory, further demonstrating his remarkable ability to transform and profit from diverse business opportunities.

Antonin expanded his ventures in 1936 by modernising dhows with diesel engines. His collaboration with Henri de Monfried in 1917 to construct a dhow unfortunately led to a misunderstanding with the government, which seized the vessel due to suspicions of illicit arms trading.

By 1941, Antonin's dhow fleet had become highly competitive, particularly through his strategic decision to transport sheep during the monsoon season. His maritime assets were not limited to dhows; he also owned ships, lighters, tugs, and even a floating dock.

Antonin was a true pioneer of his time, introducing air conditioning to Aden, driving the first motor car in the area, and owning the first refrigerator, which allowed him the luxury of enjoying chilled beverages. He was hugely successful in business, running a thriving hide trade, operating a fleet of trucks in Ethiopia that was renowned in the region, and managing various other ventures in Aden.

Yet despite his commercial success, Antonin also took time for leisure, regularly swimming in the shark-infested waters of Sharks Bay. He humorously claimed that the excitement of potential shark encounters enlivened his swims. Local folklore suggested that sharks never bothered him, jokingly noting, "No sensible shark would ever think of taking on a shark that size."

Antonin's contributions went beyond business; he was also known for his philanthropy, although he preferred to keep these activities discreet.

In a harrowing incident in 1940, while returning to Aden from from Mukeiras, Antonin's plane crashed during takeoff. He sustained serious injuries, resulting in him being encased in a body cast and enduring the intense heat of Aden. To recuperate, he had to spend some time in France.

Antonin was priapic in the extreme. Margueritte turned a blind eye to his infidelities until the inevitable happened and his secretary Hilda fell pregnant. She nevertheless remained on reasonable terms with him after the divorce and asked him why all his mistresses were so ugly. “You don’t understand, my dear,” he replied, “I have a mission in life”. “Oh!” said Margueritte, “what is your mission?” “To bring the joys of life to nature’s disinherited” (d’apporter les joies de la vie aux déshéritées de la nature). While detailed public information about all his mistresses is limited, the known details paint a picture of a man whose personal beliefs and actions were often at odds with societal norms and expectations.

Hilda, although she had intellectual pretensions, was not the sharpest knife in the drawer. She was also devoid of any sense of humour or irony and used to complain about Antonin's mistresses without realising that it was she who had broken up the first marriage as one of his mistresses!

Freya Stark had visited Aden on her way into the Hadramout and Antonin had helped her. Freya was no beauty, made worse by a terrible accident she had suffered as a girl in her stepfather’s factory in northern Italy. There was a friendship between Antonin and Freya, and then later a coolness arising between them, leaving the impression that the coolness came about through misplaced advances by Antonin. While they were still good friends he invited her to Le Paradou, his property in the south of France. Le Paradou is a rambling place with a main house and several small guest houses in the grounds. Freya was allotted one of these. At some stage in her stay she invited Antonin to come and “chat”. Antonin gave strict instructions to his daughter that she was to come in to the house promptly at noon and announce that lunch was served. At noon she walked in to make the announcement and found Freya reclining on the sofa and her father looking rather uncomfortable in an armchair. She announced lunch was ready and left. About half an hour later they appeared, Antonin furious with his daughter for not coming in again to insist that lunch was served. “For,” he said, “you know what she wanted? I couldn’t do it, even with a sack over my head!” So perhaps the coolness in their friendship was not due to “misplaced advances” but to “a woman scorned”.

Antonin was known for his strict parenting style, and his sadistic upbringing of his first two children, although it seems he softened with his later children from his second marriage to Hilda. Unlike with his older children, there is no record of him being harsh towards his younger ones, possibly due to the presence of Miss Iris Ogilvie—referred to affectionately as IO—who was hired by Antonin and Hilda, to care for them. Hilda herself was not particularly affectionate, so the children received much of their emotional support from IO. Antonin held strong opinions on child-rearing and inheritance, believing that children should not automatically inherit their parents' wealth.

By the late 1940s, in addition to his ongoing business ventures, he had accumulated a significant fortune. His vision was to establish an institution focused on advanced learning, particularly in international relations with the Arab world. Initially, he proposed this idea to the French authorities in Paris, who showed interest in the financial aspect but were less enthusiastic about his educational vision. Disappointed, Antonin turned to England, specifically Oxford, where his proposals were more warmly received. Consequently, a substantial portion of his wealth contributed to the establishment of St. Antony’s College, Oxford. He also allocated funds for building projects across various other colleges, leading to several "Besse" buildings.

Antonin passed away on July 2nd 1951 in Scotland before he could fully divest from his enterprises. Despite his firm stance against automatic inheritance, Besse’s passing left a significant estate that needed to be managed. The division of his assets was complex and involved numerous legal proceedings. Hilda, his second wife, received a substantial portion of his estate, securing her financial stability and that of her children. However, the inheritance process was not without contention. Marguerite, his first wife, also laid claim to part of the estate, resulting in a protracted legal battle that eventually saw her receive a portion of the assets. The children from both marriages found themselves in an unusual situation, inheriting substantial business interests despite their father’s expressed beliefs. This unexpected windfall required them to navigate the challenges of managing and preserving the family legacy, balancing their personal ambitions with the responsibilities they inherited. The story of his inheritance reflects the intricate dynamics of his family and the enduring impact of his beliefs and actions on those he left behind.

Information compiled from David Footman's book and also directly from Antonin's son in France, and his grandson, John.